I asked & you answered. Since Story Games runs every two weeks, I’m aiming to alternate between newsletter topics to keep the writing exciting for me—and I asked folks on Instagram what my B-side topic should be. Thanks for answering, everyone! Based on your input, I’m going to make every other Story Games newsletter a Design Diary, offering short, structured reflections on my design practice in fiction, games, and teaching. In each Diary I’ll investigate a design question inspired by my creative, professional, and personal life, and leave you with an actionable tool to play with.

In this first Design Diary, I head to an NYC bookstore for an event I planned, carrying nametags, animal stickers, and opinions about ethical leadership. After losing Catapult, a major online platform that supported my teaching, I’ve been thinking a lot about how to design sustainable creative communities. Read on to learn why I think any such design must begin by taking facilitators off center stage.

A Philosophical Framework™

Until recently, I augmented my University classes by also teaching online, continuing-education courses hosted by Catapult—a literary platform and community that included a book publisher, an online magazine, and writing courses taught by a slate of accomplished authors. I taught interactive fiction, worldbuilding, and roleplaying game design until Catapult’s writing programs and online magazine were suddenly shuttered.

For newcomers to the world of literary shenanigans, here’s the gist of what happened. Catapult’s success in creating a platform for innovative, internet friendly creative writing and courses was supported by arts funding from Elizabeth Koch, daughter of climate change boogeyman Charles Koch. Many writers and teachers at Catapult were unaware of this until the New York Times ran a vanity piece on Elizabeth Koch the same week Catapult’s classes and magazine shut down.

Here’s a description of Perception Box, the new effort that Koch had decided to direct her efforts (and funding) toward:

This language also made its way into the mission statement for Catapult’s books arm (the one area of Catapult that didn’t close):

After finding out my Catapult classes were canceled to make way for Perception Box, I decided I wanted to get my creative community out from under the thumb of a billionaire a tiny bit—or at least shift to being under the thumbs of some different and new billionaires, you know, just to spice things up.

So, I sent an email out to all of my past Catapult students about doing a get-together for NYC locals who had taken at least one class of mine. I’m forever saying that making an impact in your local community is better than shouting about stuff on Twitter. So I figured I’d better put my facilitation where my mouth is (I didn’t have money to spare, as I was out a pretty penny due to my canceled Catapult classes) and hang out with people in the city that I’ve made my home.

In planning this event, I knew a few things were true. First, I needed to create some form of structure to replace the extensive administrative and technical support I’d had from Catapult’s writing programs staff. And second, I wanted to be responsive to the specific situation surrounding Catapult’s dissolution.

If your career is education related, you may have heard about “decentering the teacher.” I thought about this when I read Catapult’s new mission statement, because it seemed like the opposite of what Elizabeth Koch decided to do. Instead of continuing to fund an arts organization that platformed writing and teaching by a slate of marginalized writers, Koch was shifting over to promote a philosophical framework™ that she had invented.

Decentering the Teacher explains this idea in more depth, if you’re interested. Also a philosophical framework of sorts, decentering the teacher characterizes the cultural values of white teachers as specific and relative, rather than as the default. The goal is to make classrooms more safe, functional, and creative for students of color and other marginalized students, whose learning may otherwise be set aside in favor of assimilating to the implicit bias and beliefs of their teacher.

The easy reach here is to proclaim “billionaires are assholes.” But the point I’m actually making is that even well intentioned, highly educated teachers need a philosophical framework™ to avoid making their classrooms all about them. So in planning a community that exists as a response to Elizabeth Koch’s decision to pull Catapult’s funding in favor of Perception Box, I wanted to explore design tools that prevent me from becoming just another Elizabeth Koch in a slightly wrinkled, loud-colored Wildfang collared shirt.

Marginalized folks are justifiably wary of boxes. My game design-inspired teaching has been called “rigid” by folks as interested as I am in equitable communities, and I value that perspective. I’m also aware that when there are no boxes, the already-powerful people always win. When I hear talk about “freeing people” from limitations, I hear an argument for a nebulousness where folks with existing capital—both economic and social—can hold sway.

I’ve experienced this in queer and nerd communities, too, especially as someone with a nontraditional educational background who doesn’t always understand pop culture references. (If you’re interested, I shared all about my upbringing in the first episode of the Queers at the End of the World podcast).

So, when I design a gathering like the one for my Catapult students, I think about selecting the right kinds of boxes. That’s what game designers do: we identify interesting constraints on interaction, and assemble these constraints into unique, expressive, and surprising constructs.

In the case of events where people are meeting for the first time, one of my favorite design problems to explore is how to let people build relationships without my own intervention. You could call it “decentering the facilitator.” To clarify why this is important, let’s consider the traditional way most facilitated events open. Imagine a class led by me, Nat, and attended by five other participants:

Nat

Person A

Person B

Person C

Person D

Person E

Now, let’s imagine that I open by stating, “Let’s all go around the circle and state our names and pronouns.” Pretty normal, right? We all know how this goes. Person A leads off: “I’m Person A, and my pronouns are she/her.” Nat nods, smiles, and says, “Great.” Then, they point at Person B, who repeats the pattern. This continues until everyone’s been around the circle, and the talking stick, as it were, is returned to Nat.

Here’s the problem I see with this pattern. Nat, in this example, has never really relinquished the talking stick. What follows is a map of where people’s attention goes when a group communicates in this configuration:

Nat

Person A

Nat

Person B

Nat

Person C

Nat

Person D

Nat

Person E

Nat

In addition to this pattern firmly centering Nat as the Important Person in the interaction, it also casts names and pronouns as a kind of memory test. Persons A, B, C, D and E must all listen and remember four other sets of names and pronouns (in addition to Nat’s pronouns) despite that the communication of this information clearly wasn’t directed at them—it was directed at Nat, of course.

This is actually a significant reason why I like teaching on Zoom. When leading Zoom meetings, it’s trivial to ask people to add pronouns to their display name. Or, as a participant, you can role model this practice of resourcing your colleagues by yourself.

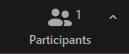

In case you’ve never done this before on Zoom, it’s easy to do. In Zoom’s bottom bar, you click on the Participants button:

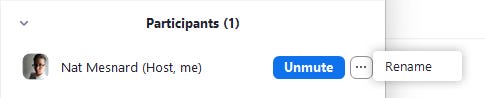

This will reveal a windowpane to the right of your meeting screen. In that pane, you just click on the dots to the right of the Unmute button and select Rename:

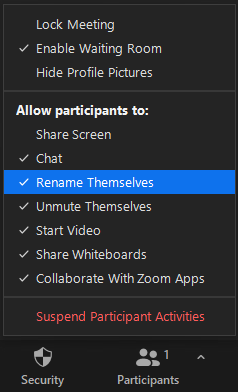

By the way, have you ever been in a Zoom meeting where it’s not possible to edit your name? If so, did you know that you can ask the meeting host can change the security options in Zoom to make this possible? Tell your host to click on Security in the bottom bar of Zoom, and assure that Rename Themselves is checked:

With this information in place, the need for “going around the circle” is reduced, because everyone’s details are visible. It’s a great start to creating an equitable community that isn’t habituated from moment one to assuming the facilitator will remain at center stage.

Now, in thinking about how to translate this into an in-person design for my Catapult get together, the obvious answer is nametags. I mean, duh. It’s a piece of paper stuck to your body with the required information on view. But also, Hello, My Name Is nametags feel like they belong in the corporate horror world of my TTRPG Business Wizards. They create an “office mixer” feeling, that’s for sure.

There are ways to solve that problem, though. And the solution I settled on for this particular event was these amazingly cute animal stickers:

I brought these, and your standard Hello, My Name Is nametags with me to the meetup, which happened at P&T Knitwear, a bookstore in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, last Saturday. Here’s how I asked participants to use the stickers to customize their nametags:

When people meet each other, they want to self-express. They want to communicate their personalities, and they want to be seen. For me at least, that’s a huge motivation for attending a class, an event, or a private party. And I’m always looking for ways to build that sense of play and creativity and possibility into the things that we need to do—have to do—in order to feel safe and friendly and like we’re truly accommodating each other.

Here’s why giving people animal stickers to put on nametags accomplishes that:

It clarifies that an administrative object, the Hello My Name Is nametag, is a foundation for play, not purely an obligation or a requirement.

It sets a clear boundary between preference and data. Stickers are the “preference” here, the expressive choice. Names and pronouns are data. You’re invited to provide both!

It provides critical information, both necessary and expressive, about each participant, so that attendees rely less on the host to form social bonds.

This last point is the one I’m the most focused on right now. With nametags and animal stickers in play, “going around the circle” never needs to happen. People can see each other’s basic information, and they’ve already got a tiny inroad into creative conversations because an expressive choice within constraints (which animal sticker to take) has already been made. This disrupts the Nat, A, Nat, B, Nat, C pattern of interaction. Introductions don’t happen at a single point in time, and aren’t routed through my facilitation. Instead, they grow up organically, across many points in time, and that process is supported by a tool that I designed.

Design in Action

If you dig community-building with animal stickers, come join me in Creative Worldbuilding, the online class I’m teaching at Center for Fiction on May 6 & 7. I launch my worldbuilding classes with a collaborative lore-building activity that puts your imagination—and not my voice as a teacher—at center stage:

This generative course will include prompts, opportunities to collaborate with other writers, and activities designed to investigate the mindset of building new worlds. Here’s the full description:

Before creating plot and character, many writers of science fiction, fantasy, and innovative literary fiction spend hours exploring setting. And as we imagine languages, biospheres, cities, and citizens, we embed ourselves in them: our identities, politics, environment, fears, dreams, and current events. This workshop invites you to explore making this process truly creative. What are the imaginative possibilities we can give rise to with the fictional settings that we shape? Through generative prompts and expansive conversations, we’ll investigate critical utopian worldbuilding—writing settings that move past our own thorniest issues and unearth new problems to solve.