Twine, Sparrows & Dadaist Poems

How do I make interactive fiction accessible to young writers interested in creative writing work?

Story Games has been on a brief hiatus during my summer travels. After coming back from my Nova Scotia trip, I took off to Pittsburgh, PA and then Gambier, OH for various educational offerings. This Design Diary recounts my Ohio trip, where where I spent two weeks reminding myself—and 13 high school students—why poetry is amazing and interactive fiction is everything. Read on to hear more about the Kenyon Review Young Writers workshop, and how I entice high school poets to try making narrative games.

Fireflies and Sunsets

Each summer I leave New York City for Gambier, Ohio, where I teach in the Kenyon Review Young Writers Workshop. This two week residential camp provides talented high school students with “a dynamic and supportive literary community to stretch their talents, discover new strengths, and challenge themselves in the company of peers who are also passionate about writing.”

The first time I taught in Young Writers was in 2018, as a teaching fellow. I co-taught with poet Richie Hoffman, but didn’t return as full faculty until 2019, the Workshop’s first year back in-person after the pandemic. This year, my third, was the first time the experience felt familiar, its routines triggering layered memories of past summers, instead of that dream-like sense of transport characteristic to first-times and post-pandemic renewals.

Teaching in Young Writers is always challenging. Each day encompasses about five hours of instructional time, plus a daily instructor meeting and readings or other mandatory camp-wide events every night. Somewhere in there, you fit in lesson planning, socializing with faculty, dinner events with invited readers, and composing a piece for the faculty reading inspired by prompts given at camp. It’s a wash of activities and interactions, this intense process of group-merging that leaves everyone by turns buoyant and hollowed out.

In the between-hours, we experience the green humidity of Ohio. It’s quiet there, a welcome respite from my urban home. There are fireflies. There are lovely sunsets. There is the nearby town of Mount Vernon, which can be a scary place for faculty of color and queer faculty. There is a mysterious stray cat who surveys the campus pathways and refuses to be approached.

One of the things I like about Young Writers is that it brings me briefly back to traditional creative writing pedagogy. Most of what I do now is multimedia making, and that is of course by choice. But I enjoy visiting my MFA past: at camp, we do longhand freewriting, discuss literature, and write to prompts, generating magical realist fiction and nature poems. One of the assigned readings is a piece by my teacher Brigit Pegeen Kelly. I always leave Young Writers motivated to write more short fiction and poetry, a spark that animates me throughout the rest of the year.

Still, let’s be honest: I can never totally stay in that lane.

While each teacher in Young Writers spends most days with their assigned class, we also are invited to propose a topic-specific session that meets for a total of three times during the camp. From film poems to ekphrasis to the craft of critique, these sessions can serve as informal pedagogy labs, providing a low-stakes opportunity to try out ideas for a particular lesson or an entire class.

The genre session I have offered for all three years of my Young Writers tenure is an introduction to Interactive Fiction. It’s my sole opportunity to play with translating this material for high school students, since I teach undergraduates and adults the rest of the year.

This time, I dedicated each of my genre session’s three meetings to a different reading. My design goals were to create continuity with the prompt-based work in poetry and fiction we do during regular camp sessions, and lead students to IF principles from a place of confidence, curiosity, and excitement.

Here’s what I did.

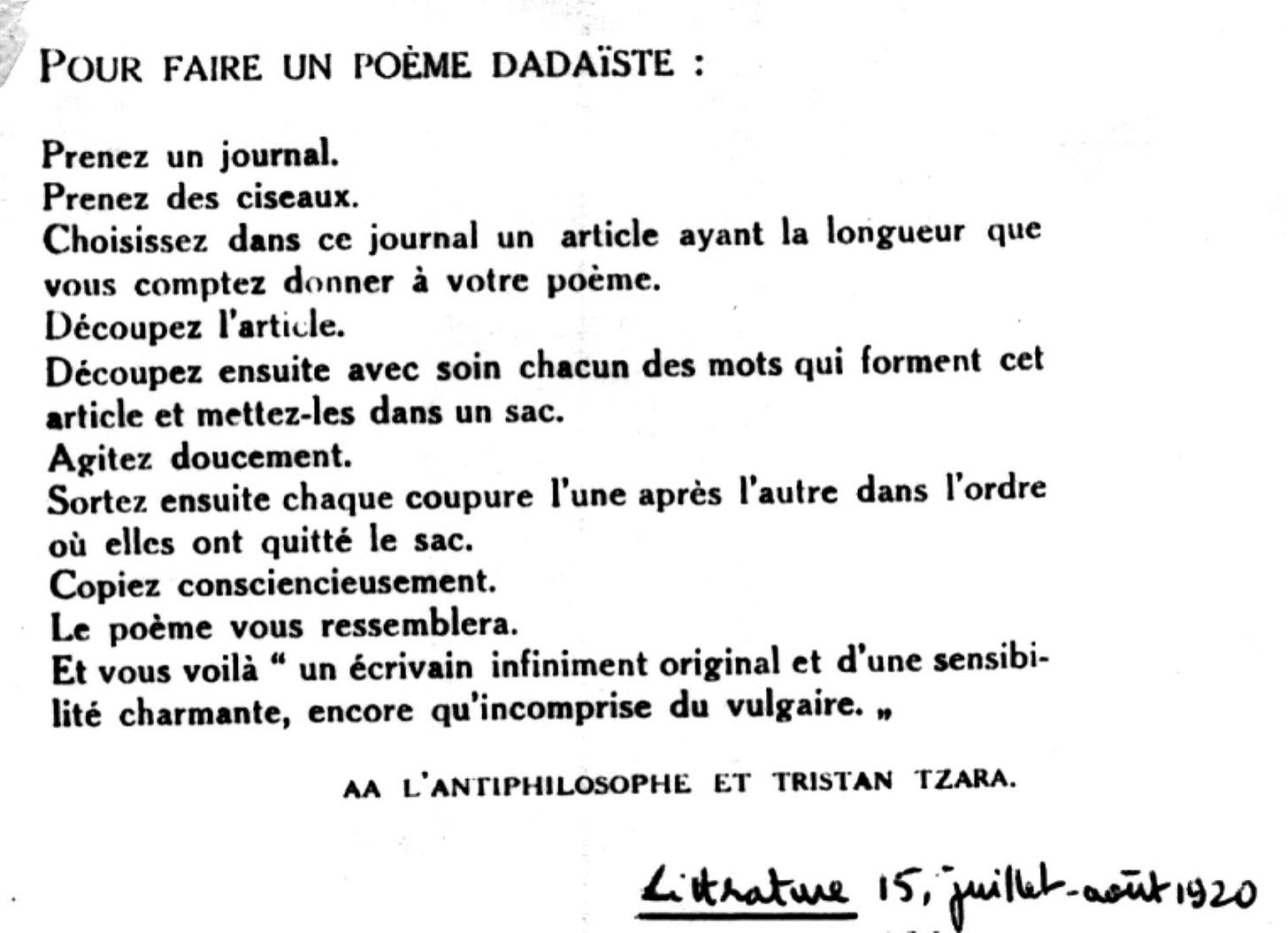

At our first meeting, we began by reading Tristan Tzara’s piece “To Make a Dadaist Poem.” Here’s the English translation (courtesy of MoMA Learning):

TO MAKE A DADAIST POEM

Take a newspaper.

Take some scissors.

Choose from this paper an article of the length you want to make your poem.

Cut out the article.

Next carefully cut out each of the words that makes up this article and put them all in a bag.

Shake gently.

Next take out each cutting one after the other.

Copy conscientiously in the order in which they left the bag.

The poem will resemble you.

And there you are—an infinitely original author of charming sensibility, even though unappreciated by the vulgar herd.

My attention was brought to this work by the writer, gamer, and poet Alejandro Ruiz del Sol. He gave a short video presentation at Narrascope this year on ways Dadism might energize the practice of narrative design.

Collage poetry, erasure poetry, and automatic writing are a large part of the Young Writers curriculum, so Dadaism felt like a point of connection. We “playtested” Tzara’s piece, actually creating a randomized cut-up taken from previous copies of the Kenyon Review. Here were some of the questions I led with during the discussion:

Does the final product “resemble you” as Tzara suggested? In what ways is it possible to customize and curate the output here?

What would it be like to write a poem or a story that gives the reader instructions and results in the generation of an additional creative work?

Was this fun? If so, why, and if not, why not?

My next reading aimed to lead students gently into the world of Twine. I selected a short piece by Monique Laban that originally ran in Tiny Nightmares, an anthology of flash horror published in 2020. Laban’s piece “Marriage Variations” is a choose-your-own-adventure story inspired by the Bluebeard folk tale. Excitingly, she prototyped its branching paths using Twine! Here’s an excerpt from the piece:

You hear a bang. In the light, you see that the cat has knocked the keepsake box off the hallway shelf. Out spill childhood photographs of your sister and two brothers. They never liked your husband.

His door opens on the cat’s commotion. He stares at you, blue eyes wide. If you confront him about the noises, go to 4. If you return to bed and seek counsel from your family in the morning, go to 5.

“Marriage Variations” is wonderfully spooky, and the best part is that it’s an infinite loop, never allowing the reader to reach a true ending. Here were some of the questions we worked with in discussing this fantastic work:

Why did Laban decided to tell this particular story as a choose your own adventure?

What effect is created by giving the reader choices? Is that undermined by making the story an infinite loop?

Why work with an existing fairytale or folk tale when crafting a work of interactive fiction?

Following this conversation, students opened Twine for the first time and spent 45 minutes prototyping a story with similar constraints to Laban’s.

My third and final reading was Brave Sparrow, a solo roleplaying game by Avery Alder. I’ve taught with this RPG that Alder calls an “alternate reality experience” once before, and I think it’s a wonderful demonstration of how roleplaying games can connect with Avant Garde literature, ritual, and play beyond the rolling of dice.

Here’s the first page of Brave Sparrow:

How long have you felt it?

Your fingers filled with dull ache whenever you use them for too long, your shoulder-blades tickling with the sensation of phantom limbs, that sense that you’re swimming in a body too big to make use of, the confusion of being.

You weren’t meant to walk among humans.

Maybe you’ve just shrugged it off, assuring yourself that everyone feels this way sometimes. Maybe you’ve been going crazy for the answer. There is no easy way to doubt your body. There is no comfortable way to fall apart.

But the feeling is getting clearer. You dream about flying either all of the time or never at all. You hate depending on your legs for movement. You don’t trust like you used to. You crave beauty like you’ll die without it. You’re ready to fly.

You’re a sparrow, brave and terrified.

Brave Sparrow is a great occasion to discuss the “magic circle” of game design. With the introduction of that term, Alder’s work can also herald a movement firmly in the direction of game design logic and mentalities, allowing students to experiment with bringing that perspective to their work. Here are a few of the questions we addressed in the context of discussing Brave Sparrow:

How does the game weave lore and worldbuilding into its instructions?

How can a roleplaying game work without traditional dice-rolling mechanics?

How do we know when a piece of writing is a game?

All together, I offer up these three readings as a useful design tool in making the connection between more traditional literary practices, and the more hybrid, design-driven ones we play with in IF and game design.

If you’re an aspiring IF writer, I still highly recommend these materials as a route to enhance your own learning. They are a particularly great way for more technical developers to nudge into literary life while remaining connected with familiar tools like branching, rules, infinity, and instructions. Regardless, why not write a Dadaist poem? Or read Laban? Or play Brave Sparrow?

Imagine you’re in Ohio with me, summer on loop, one year merging with another. We’re sitting on a bench together, discussing poetry. Or fiction. Or the many branching paths the two of us might take from here.

A Class on Autofiction

In one of those paths, you can take a course with me this weekend at the Center for Fiction. The last I heard, we’re at 7 seats filled so far, which means you’d be joining a robust community of fiction writers and memoirists.

What happens when we remember? Neuroscience tells us that memory is a process of reconstruction, not recall—each telling of the past is a new composition, rather than the same book checked out of the library. Beginning with this remarkable truth, we’ll explore writing memory in fiction throughout this expansive, generative course. Through prompts, breakouts, and sharing memories of our own, we will investigate how the craft of fiction interacts with stories of the past.

This course is inspired by some of the work I’ve done with my collaborator and partner Patrick D. K. Watson, including our collaborative nonfiction essay The Half Sacred Disease, which was published as part of the Kenyon Review’s Poetics of Science issue. Patrick’s PhD research was in memory, and in my classic genre nonbinary fashion, I’ll be bringing to the creative table some readings, neuroscientific oddities, and ideas suggested by him.

Direct your questions my way if the course interests you. I would love to see you there!