You Have to Practice

When do consent tools actually work, and when are they just performing safety?

In this Design Diary, I recap my experience at Avery Alder’s Designing Games that Matter workshop, where I spent five intense days conducting game design labs and delighting in glorious queer community. I left the workshop full of joy, design ideas, and reflections on queer intimacy and storytelling. Read on for my exploration of ethical cuddle puddles, and how tools of consent actually work.

Cuddle Puddle Summer

In mid-May, I traveled to Nova Scotia for Designing Games that Matter, a workshop on designing “meaningful, dynamic, and transformative tabletop roleplaying games” led by designer Avery Alder. A major inspiration for my own game design practice, Alder is the author of critically-acclaimed tabletop roleplaying games such as Dream Askew, A Quiet Year, and Monsterhearts 2.

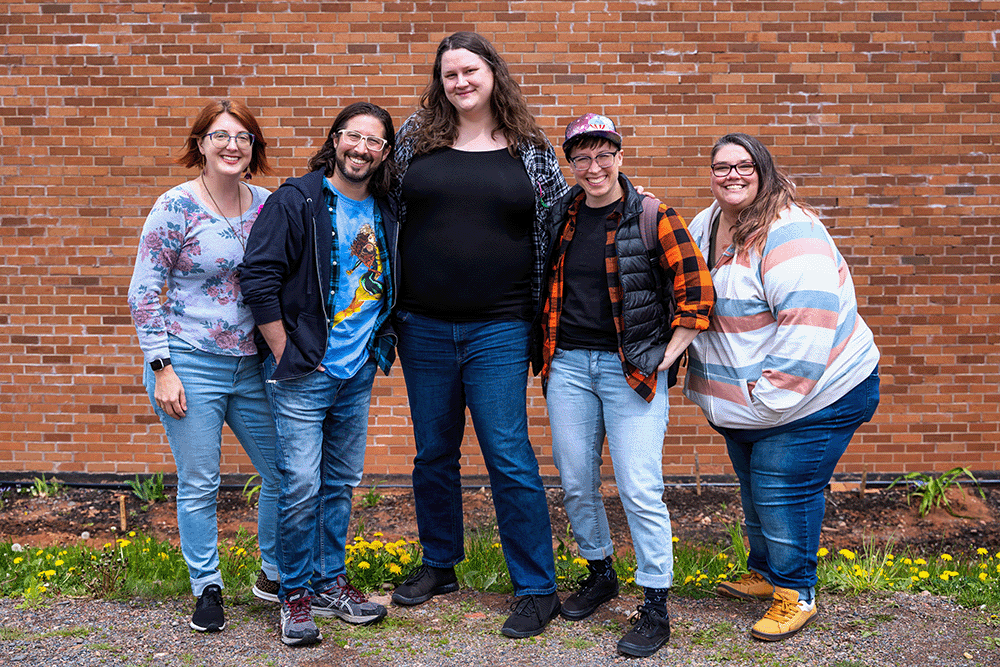

I was joined on the trip by three of my colleagues at Scryptid Games, the small press I co-founded this year focused on storytelling games for people who love books. Several of us had never been to Canada before, and we excitedly made our way across the border to explore new ideas and new lands.

The workshop was held at a place called Tatamagouche Center, a “meeting place for those who deeply care about spirituality, leadership, and social justice” located on Tatamagouche Bay on the north coast of Nova Scotia. The Center comprises a cluster of residential and multi-use buildings situated in lovely, grassy fields in view of the water, with most activities taking place in a central hall that offers comfortable meeting rooms and a cafeteria on the lower floor.

Design work started at 10AM each morning, and comprised a mix of lectures and hands-on workshops. Most days focused on one or two “design labs” that tasked us with collaboratively prototyping a game in response to prompts situated in the workshop’s central ideas: design is political, games are tactile, and play is collaborative.

Each day felt jam packed, a patchwork of new ideas, relationships, and moments. I played a windswept game of Dream Askew on a sunny picnic table overlooking the water with four other amazing designers. I helped concept games about utopian rejects, quantum witches, and an alien burlesque troupe that performs at spaceports all across the galaxy. I stayed up late with Tiffany talking about poetry, flowers, and favorite trees. I wrote a poem. It was magical and generative in the way that only such remote, intense experiences can be—the workaday world recedes, and for a few days, life is about these people, these games, this food, this bonfire.

I also noticed that, while folks are still being generous and mindful about Covid safety, a kind of opening-up is happening right now. Body language is less traumatized and more adventurous. We are seeing each other’s faces. Despite the ongoing terror of climate apocalypse and nationwide assaults on trans rights, there is an electric energy arising as queer people come together in these small, structured, temporary, embodied communities.

Maybe it’s just me, but I’m feeling like this particular in-person sensuousness is characteristic of this year’s impending summer energy. I’m feeling less of the aspirational hot girl summer vibes from last year, and more folks making good on our desperate need right now for real interdependence and intimacy. I hereby make the following contribution to the discourse: 2023 is giving cuddle puddle summer.

Anyway, with all this swirling in the air, I ended up thinking a lot about ethical facilitation practices—and specifically, how to effectively leverage tools of consent.

One of Avery Alder’s lectures during the workshop focused on TTRPG safety tools. Broadly, these named tools—Lines & Veils, Open Table, the Luxton Technique, and others—aim to provide structure, language, and clear boundaries around collaborative storytelling. In an ideal world, these frameworks help players communicate more effectively, making it easy to establish narrative topics folks don’t prefer, to slow down or shift the course of a story, and to otherwise afford players control over improvising scenes and hashing out narrative in games.

This is obviously important if you think about what you actually do when you sit down to enjoy a roleplaying game. You make a character who represents some aspect of you—or at least, your creativity—and then negotiate with friends, new acquaintances, or even strangers about how your characters interact with conflict. Depending on the story you’re telling together, conflict can range anywhere from “social intrigue” to “grimdark violence,” and between three and six authors must quickly and collaboratively determine what is okay, what is exciting, and what is absolutely terrifying in order to build a narrative arc and reach a satisfying conclusion.

In an attempt to creating equitable roles amid this impossibly complex process of negotiating narrative power, designers have invented safety tools. One such tool is the X Card, a commonly deployed framework that is supposed to allow players to stop or remove elements of story and redirect toward something else.

Here is the first part of the script provided by John Stavropoulos, inventor of the X-Card, for incorporating it into play:

TO USE THE X-CARD, AT THE START OF YOUR GAME, SIMPLY SAY:

“I’d like your help. Your help to make this game fun for everyone. If anything makes anyone uncomfortable in any way… [ draw X on an index card ] …just lift this card up, or simply tap it [ place card at the center of the table ]. You don’t have to explain why. It doesn't matter why. When we lift or tap this card, we simply edit out anything X-Carded. And if there is ever an issue, anyone can call for a break and we can talk privately. I know it sounds funny but it will help us play amazing games together and usually I’m the one who uses the X-card to help take care of myself.

I’ve seen this used a lot, both in person and online. In Zoom games, I’ve played with GMs who state that folks should throw up an X using their arms any time they need to X-Card something. Meanwhile in person, an X-ed index card is ceremonially placed on the table atop character sheets, RPG books, pens and pencils, and other assorted ephemera, at the ready for players to express their needs and their triggers.

It’s a beautiful and heartfelt expression of care, but I have found that in practice, the X-Card does nothing. People don’t use it at all. And this makes sense to me, because it’s horrifying to bring play to a halt in such a confrontational way. “No, I want to X-Card that, it’s a trigger for me” is certainly a thing that you could say, but actually saying it feels, at least to me, completely out of reach.

So, I asked Alder about this during her safety tools lecture: “I love the X-Card, but how do you actually get people to use it? I’ve never used it, and I’ve never seen it used.”

Her response was that you have to practice.

The idea, as Alder explained it, was that indeed, using the X-Card can feel difficult when it matters, so players should practice using it on low-stakes examples first. This way, saying no and re-narrating is normalized. The example she gave was for the game’s facilitator to collaborate with an experienced player to X-Card a character’s name, like this:

Facilitator: “I want this NPC to be named Catherine.”

Player: “Can I X-Card that? I don’t want there to be a character named Catherine in this game.”

During this conversation, my colleague Brigitte brought up some ways similar tools are used in consent workshops. As she spoke, I was reminded of an essay from Girlhood by Melissa Febos, a book that explores the author’s childhood, the entrapment of gender norms and femininity, and the problems of sex and desire and violence that interfere with (as I take it) queer liberation.

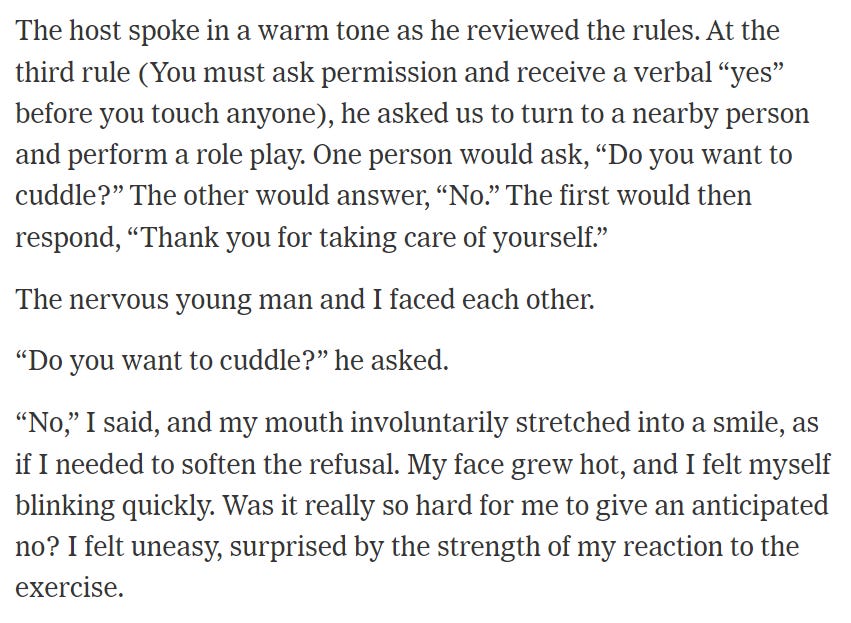

In Girlhood, Febos writes about a cuddle party she attended with her partner Donika—in part, to intentionally explore the themes of consent, sexuality, and pleasure that wind throughout the essays in the book. After the two women arrive at the event, the host takes attendees through a practice round of saying “no”:

Even Febos—a queer, feminist writer and ex-pro dominatrix—struggles to turn down a man’s request to cuddle. Later at the party, she finds herself saying “yes” when what she really means is “no” or “I’m not sure.”

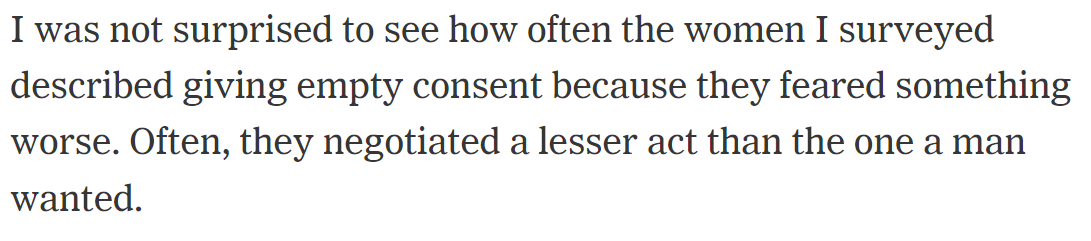

Providing empty consent, writes Febos, can be an act of self protection. She later surveys sex workers and women in her life to explore this concept, writing:

This is not a dynamic we can entirely leave behind when we enter protected queer spaces, and sit down at roleplaying tables, because we bring our bodies with us. So to me, imagining that players—even in a game entirely made up of consent-aware queer friends—can automatically utilize the X-Card to direct the course of a collaborative story seems absurd. Even when consent tools are present, many players will still give empty consent as a means to self-protection, just as Febos and many other women have done.

This is not to say that the X-Card is useless. On the contrary, it provides an opportunity to have this very conversation—a conversation that’s absent from tables where players just roll into the story without acknowledging the hierarchies of power and channels of trauma we carry with us into the magic circle of games.

Will some players give empty consent in roleplaying games? Absolutely. it’s something I’ve done myself. But I don’t see this entirely as a failure. This is because, unlike Febos’ cuddle party, tabletop roleplaying games do not involve being physically touched. Yes, I’ve had my storytelling agenda trampled on. And yes, I’ve trampled on the needs of other players. But in the end, all of us got up and walked away from the table and its swirling dynamics, and reflected on what we had done (or not done). Why did that player make me so angry? Why did I end up giving in? Why didn’t we rescue the victim? Why is violence sometimes fun?

For me, this is itself a kind of practice. It’s a way to experience power dynamics while remaining in a position of relative safety. There may be “emotional bleed,” but in the end no one is actually bleeding. We can make mistakes inside the game, and even play as villains, as a means to learn how to move carefully toward joy when the cuddle puddle is real.

To be clear, sometimes emotional bleed does cause harm. I know through personal anecdotes and Twitter that there have been deeply violating incidents—storytelling rabbit holes and mistakes made by GMs that have retraumatized players and resulted in total relationship breakdowns. It’s a testament to the power of roleplaying and the necessity of practicing consent.

Following my conversation with Alder on practicing using the X-Card, I’m thinking of trying out a new structure at the beginning of my next tabletop session. What I’m thinking is that players need to practice X-Carding sequentially, with each person giving one quick suggestion that is X-Carded, and X-Carding one suggestion. Rather than a single example that illustrates how the X-Card works, I suspect that this style of repeated practice will help players agree on how we want using the X-Card to feel.

Here’s how I imagine this going:

Nat: Now that we’ve finished making characters, let’s practice using the X-Card so we know how to use it during the actual story. I’ll start. I’m going to make up something narratively random, and then, Player 1, I’d like you to use the X-Card to redirect. This isn’t the real story we’re telling—it’s just for practice. Sound good?

Player 1, Player 2, Player 3: Yep. Sounds good.

Nat: So, I’m going to suggest that everyone in the party puts on clown makeup.

Player 1: I’m supposed to X-Card that, right?

Nat: Yes.

Player 1: Okay, I want to X-Card the clown makeup.

Nat: Thank you. Is there a different way we can disguise ourselves to sneak into the circus gala?

Player 1: A circus gala? Okay, um, maybe…we get fake beards instead?

Nat: That sounds good to me! Now, Player 1, can you suggest something absurd for Player 2 to practice X-Carding?

Player 1: Okay so we’re in the gala now. I’m going to suggest that we sneak psychedelic mushrooms into the bowl of punch…

A Reading!

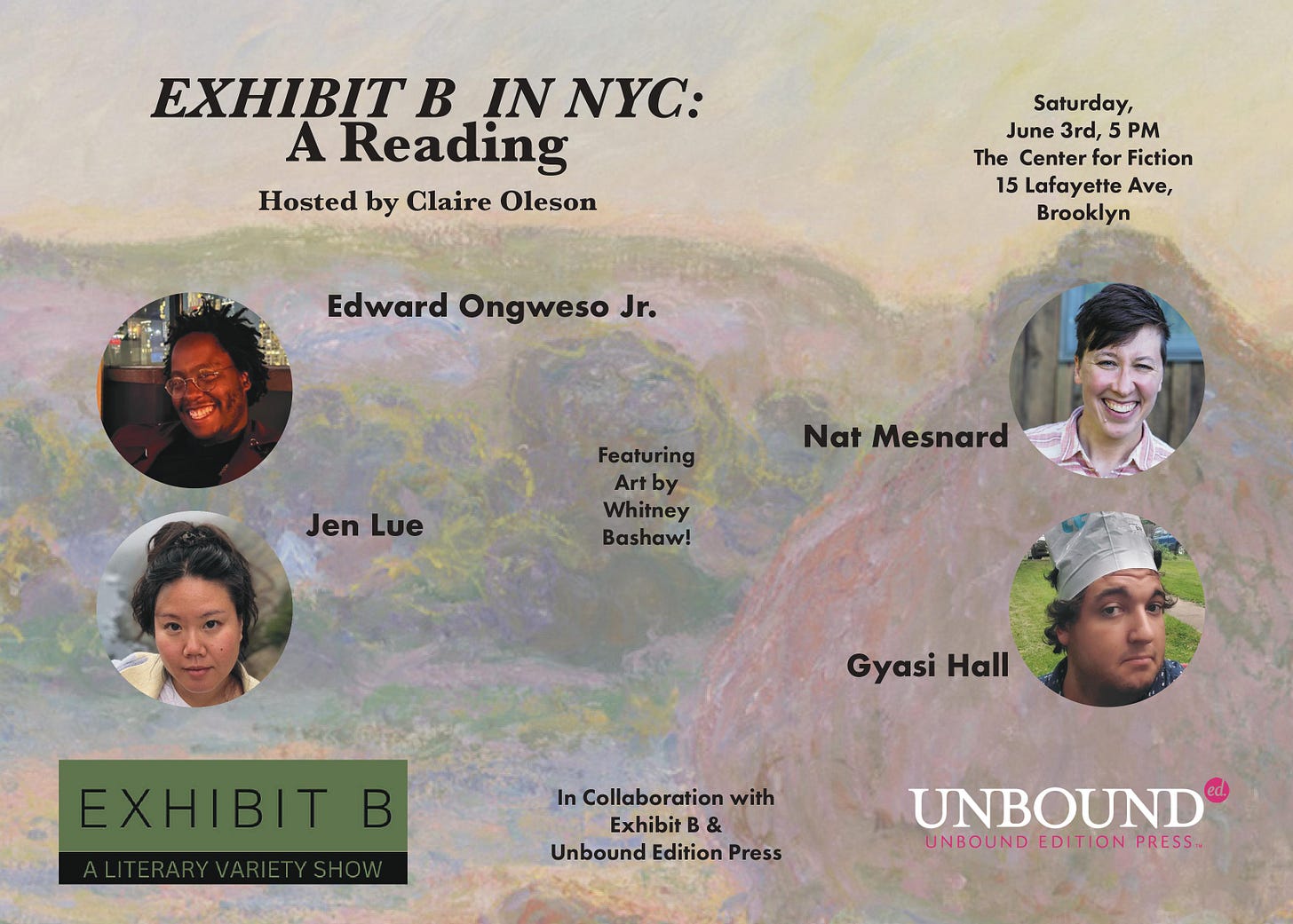

Speaking of small, structured, temporary, embodied communities—next Saturday, June 3, I’m very honored to be joining a slate of brilliant writers at Exhibit B, a reading series hosted by Claire Oleson that highlights outstanding authors with a focus on queer and trans writers and writers of color.

I’ll be reading from my novel-in-progress for the first time ever, and I’m feeling very excited about doing my second-ever booked reading in NYC. (My first was the pre-pandemic KGB Bar Red Room reading that’s memorialized in the enormous picture of me performing on my website’s landing page!)

NYC friends, I would love to see you at Exhibit B—plus, your support for Claire’s excellent new reading series would be amazing.